When I first began my course in Digital Public History I first wrote the following statement related to the Audience and Content in Public History Projects:

[Public History] can be redefined as a “society in which a broad public participates in the construction of its own history” (Grele, p.48). This shared process implies that public historians must work with communities to develop the content that will manifest into a public history project. In other words, public history projects belong just as much to the community as it does to the historian as they cannot exist without one another.

This statement continues to reign true as I conducted my own public digital history project. In my own case, I chose to focus on the disgraced individual Benedict Arnold. Arnold is someone of which I have been fascinated with for a long period of time. So, I decided to build an Omeka Website with “mostly” interactive exhibits dedicated to him. After revisions, the Omeka site is organized in the following ways:

An introductory page that provides an introductory video (it is kinda cheesy) and a transcript (a differentiation tool) as well as links to the three exhibits featured on the site: The introductory video was my attempt at using audio as a means to detail a historical narrative as well as to explain the academic argument behind the site. ( It is far from becoming a podcast I’ll just say that. )

The three exhibits are organized into three intertwining themes to explain the history of Benedict Arnold.

Historical essays are featured in each exhibit with footnotes linked at the bottom of each page.The footnotes are placed in a google doc that is accessible for site visitors.

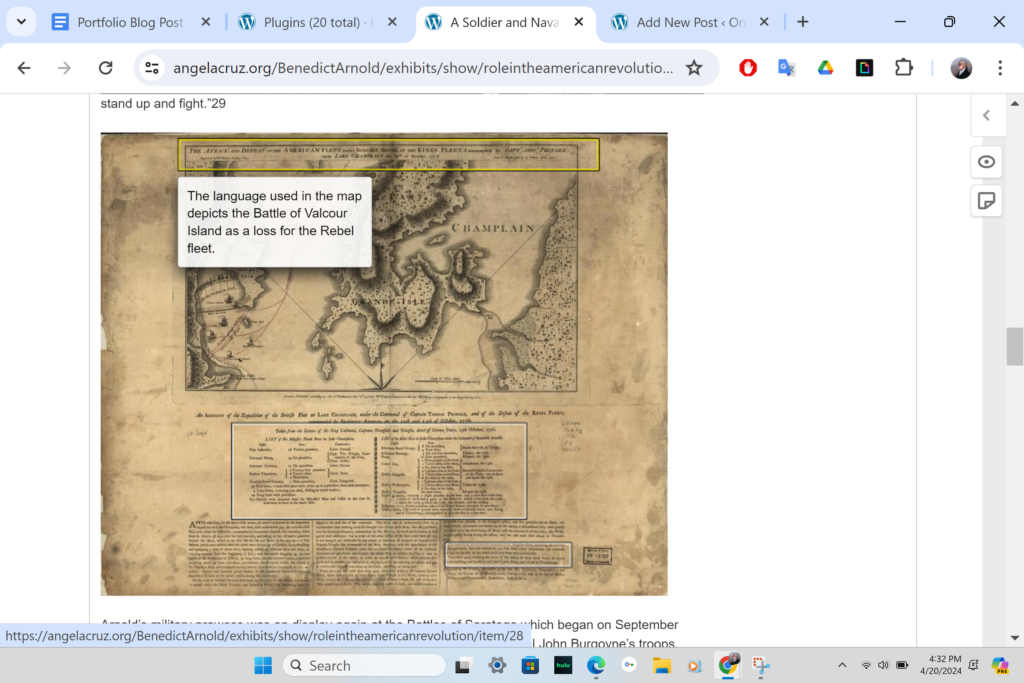

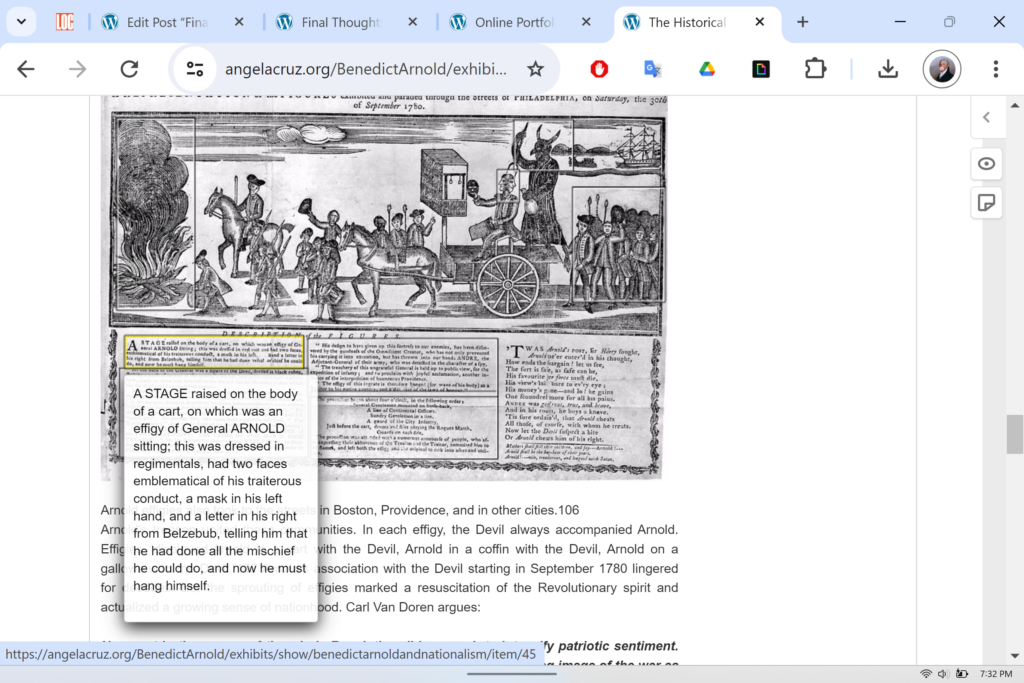

Shared authority “the interaction of scholarly authority and wider public involvement in presentations of history” (Frisch,1990, p.53) was considered in the creation of this project. Personas such as Stephanie Mitchell, a k-12 educator, and Faith Cooper, a 13 year old student, were used to hypothesize the needs of the target audience. These needs were determined by the qualitative data I acquired from interviews in my school site. The needs I considered were differentiation and engagement strategies, relevant connection to curriculum standards, and accessibility. I have used plugins such as PDF embed, Image Annotation, and Text Annotation to enhance and differentiate my primary sources. In doing so, users are given a deeper analysis of the sources themselves. Image Annotation helps students understand certain types of vocabulary that align with their curriculum standards. The annotations also provide historical context. In addition, I have embedded YouTube videos on my site to make the content more engaging for my students.

Within my exhibits, I utilized photos from archives and databases like the Library of Congress, the Digital Public Library, the New York Public Library, Jstor, Wikipedia and American newspapers. All of these photos were placed as items in my Omeka site to establish where the images were located. A total of 58 items are in the item library.

Photos/items are placed as lone files, files with text, moving carousels, annotated images, or PDFs. These images are supposed to serve as supporting evidence for the historical essays as well as to provide historical context to the time period being discussed. Their sites of origin are linked in the metadata to follow copyright protocol and give credit to the creators.

Fortunately, my Digital Public History class has enabled me to consider the academic and pragmatic purpose behind my prototype Omeka site. I have had to consider my intended audience as well as the technologies I would use to engage and educate my intended audience. I have also had to take into consideration the items/artificats I would use to exemplify my site’s academic argument.