Brats, June 2024, director, Andrew McCarthy, producers: Adrien Buttenhuis and Derrick Murray, film accessed via Hulu streaming service. Film is a documentary that uses primary sources such as film reels, television interviews, news articles, film clips, interviews from eyewitnesses who were involved with the “Brat Pack” of the 1980s. “Experts” are consulted as secondary sources to explain the 80s cultural phenomenon and the impact of “Brat Pack” films on the cultural zeitgeist.

Thematically, Brats focuses on the films that transformed the cultural lexicon of the 1980s, the trade off of fame, and McCarthy’s personal mission to confront the past.

The film was directed by Andrew McCarthy and it follows him in his journey to reconnect with his old castmates, contemporaries, and individuals who are “experts” about the impact of the “Brat Pack” films of the 1980s on popular culture. The conflict McCarthy hoped to confront and resolve with his film were the consequences associated with an article published on June 10th, 1985 in New York Magazine titled “Hollywood’s Brat Pack.” The article was written by journalist David Blum and he is credited with creating the famous phrase “Brat Pack” to identify a group of young actors in the early 1980s who starred as the leads in many feature films geared towards a younger audience. McCarthy makes it clear that he believed the article was “scathing” and damaging to himself and young actors of the day and their professional reputations. More than anyone would realize, the term “Brat Pack” lived on in the cultural zeitgeist to permanently identify the actors association with the “Brat Pack.” The phrase itself was created by a member of the media, David Blum. The overall media ran with it and the phrase snowballed into something that would impact actors like Emilio Estevez, Judd Nelson, Rob Lowe, Andrew McCarthy, Molly Ringwald, Demi Moore, and Ally Sheedy for the rest of their lives. These actors would be forever known as part of the “Brat Pack” in popular memory, culture and history. McCarthy is ultimately critical of the article’s depiction of young actors and how the term “Brat Pack” impacted his life and personal relationships. He uses his disdain as motivation to contact members of the “Brat Pack” to then revisit their shared unwanted connection and to hopefully confront his past.

The film’s historical accuracy is dependent on the testimonies of “Brat Pack” members, journalists like Malcolm Gladwell and Susannah Gora; pop culture critic, Ira Madison III; directors like Brett Easton Ellis and Howard Deutch; producer Lauren Shuler Donner, talent manager Loree Redkin, casting director Marcie Liroff and the infamous David Blum. We are meant to trust these testimonies that are then edited and interwoven with interview footage and photos that serve as evidence to how the actors felt in reaction to Blum’s article. Photographs and newspaper clippings from the 1980s were used as primary sources. Film clips from St. Elmos Fire, Pretty in Pink, Class, the Breakfast Club are used to depict the relationship between the actors who were interviewed and the roles they played. McCarthy also uses two quick cuts of words featured in Blum’s article.

The film’s historical inaccuracies stem from McCarthy withholding David Blum’s article. McCarthy never shows the full article to the audience. He only shows snippets of sentences utilized by Blum to describe his perception on how easy it was for young actors to skip a proper theater arts education to achieve success. McCarthy also shows sentences critical of Emilio Estevez who is declared by Blum to be the “president” of the “Brat Pack.” A major inaccuracy arising from the article being withheld is that McCarthy gives the impression that many young actors were mentioned by name and were subsequently trashed by Blum. In reality, the main subjects of the article were Emilio Estevez, Judd Nelson and Rob Lowe. Demi Moore (who was interviewed as if she was mentioned) was only briefly mentioned as Estevez’s on and off girlfriend while Ally Sheedy (who was also interviewed as if she was mentioned), Molly Ringwald, and Jon Cryer (interviewed as if he was mentioned) were never identified as members of the “Brat Pack.” Blum identifies actors like Matt Dillon, Nic Cage, Tom Cruise, Sean Penn, Kevin Bacon, Matthew Broderick, and Matthew Modine. Like Demi Moore, Andrew McCarthy is briefly mentioned and it was not due to any criticism from Blum. It was due to criticism from Emilio Estevez who openly criticized McCarthy’s acting technique. McCarthy fails to be specific about how the article negatively depicts young actors as a whole. Blum wrote the article after spending time with Estevez, Nelson and Lowe in the New York Club scene. Blum recorded what he saw and heard while he was with the young actors. The content served as the basis for his article.

The Moments:

Time 28:35

The theme associated with the “Brat Packs” impact on the cultural lexicon is made most clear by McCarthy’s interview with Malcolm Gladwell. Although Gladwell is not a pop culture historian, he offers insight on how the “brat Pack” label caught fire. Gladwell explained that the “Brat Pack” label signified a generational transition in Hollywood that was an explicit reference to a pun on the famous “Rat Pack” with Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin and Sammy Davis Jr.. Gladwell explained that the reference itself became a metaphor. Specifically, Gladwell stated “Whenever a term makes that journey to metaphor status, it has a chance to kind of endure. And, you know, it’s also funny. The “Rat Pack” and the “Brat Pack” in sensibility are polar opposites, right? One is anxious, and immature, and trying really hard to figure out their place in the world and the other group doesn’t give a fuck.” Gladwell goes on to explain how the “Brat Pack” was such a cultural phenomenon with youth culture as younger audiences were unified by coming of age films.

1:13:35

Another pivotal moment in the film is when McCarthy speaks to David Blum, the writer of the New York Magazine article that solidified the phrase “Brat Pack.” Blum explains how the term came to be and the context behind its creation. McCarthy first asks Blum about his employment as journalist in 1985 and the original purpose of the article. Blum clarified he was under contract with New York Magazine and the article was meant to be a feature on Emilio Estevez. Estevez invited Blum to have drinks along with Rob Lowe and Judd Nelson. Blum noted how much attention the actors were receiving. Blum explained he was mostly there to observe and did not dislike any of the actors or think of them as brats. Blum’s epiphany on the famous phrase “Brat Pack” came after he had a very big dinner with LA journalists. One of the journalists, Alan Richmond, took into account how much food Blum and other journalists ate as a result of the dinner, coining the phrase “Fat Pack.” Blum was very amused by it. The joke eventually re-emerged in Blum’s head as he was driving around LA, spinning it into the phrase, “Brat Pack” as the title of his article. Blum then began to draft out his ideas, recalling the events of the night he spent with Estevez, Lowe, and Nelson that fell into the actions of what a “brat” would do. Blum stated he did not perceive the phrase as that big a deal or as insulting but he did think the article would receive a reaction.

Teaching and Learning:

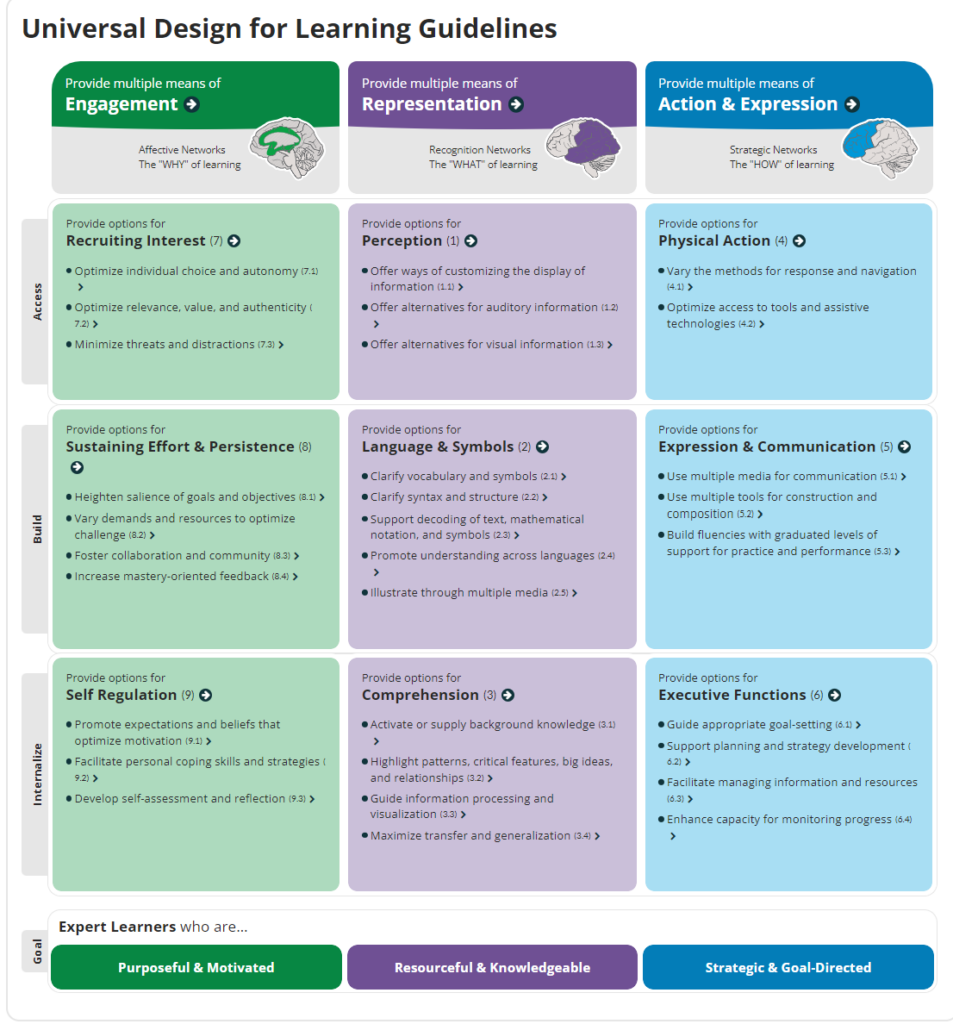

I would use this film in the context of history education because it demonstrates how terms/phrases can be taken out of context and serve as products of their time. The term “Brat Pack” symbolizes a point in time in which there was a generational transition in Hollywood films that appealed to a unified youth culture. It also permanently impacted the personal lives of young actors from the 1980s. My students are tasked with textual analysis on a daily basis with historical documents and a lot of the time famous phrases are taken out of context and given a new meaning. I would first do an introductory activity that asks students to think about the trends that exist in popular culture such as the most popular sayings. I would make a list of them and then save them for later. If I had to introduce the film to students, I would play the first 12 minutes of the film in order to establish what popular culture was like in the 1980s and the definition of “Brat Pack.” I would then give them David Blum’s article. I would give them a list of questions associated with the content of Blum’s article. I would ask my students why the term “Brat Pack” could be perceived as a negative and/or positive. I would then ask my students to investigate the origins of the popular sayings they mentioned in the intro activity to learn about their cultural significance and their connotation. Students would then be given background information on all the people associated with the documentary. Students would then be shown the rest of the documentary. They would then be given a survey associated with how they felt about McCarthy’s documentary. The survey would feature questions like were the actor’s victims of David Blum’s article, was the term “Brat Pack” enough to damage an actor’s relationship? Once they answered the survey, I would then give them copies of David Blum’s article once again along with quotes from the actors featured in the documentary discussing his article. I would ask them to compare and note the contrasts in the article and the actors’ statements. Students would then be expected to answer a short answer question about whether or not the article was truly damaging to the reputation of the actors mentioned in the article and documentary. I would want my students to ask questions related to how popular phrases and terms can endure over time.