The collection, contextualization and the interpretation of historical information are elements of historical thinking that have remained at the heart of historical teaching. The collection of historical information refers to the gathering and development of historical knowledge. The American Historical Association (AHA) recognizes that the retention of historical information is important but that it should not be the overall focus of history learning. The evolving standards of the AHA agree that historical knowledge should be built in order to “discern context.”

Unfortunately, there is a general misunderstanding that history is stagnate and is only about fact based retention due to standardized testing. For years, standardized testing has relied on assessing the memorization of dates, names, and events in place of in depth historical inquiry. The building of historical knowledge is only a small aspect of historical teaching. Contextualization and interpretation serve much larger roles in the understanding of history. The AHA’s other core competencies reflect the elements of contextualization and interpretation. Other scholars such as Weinberg, Kelly, Ayers, and Robinson agree that disciplinary skills like contextualization and interpretation are much more essential in history learning. These two skills allow students to develop and use historical methods, historical arguments, and historical perspective.

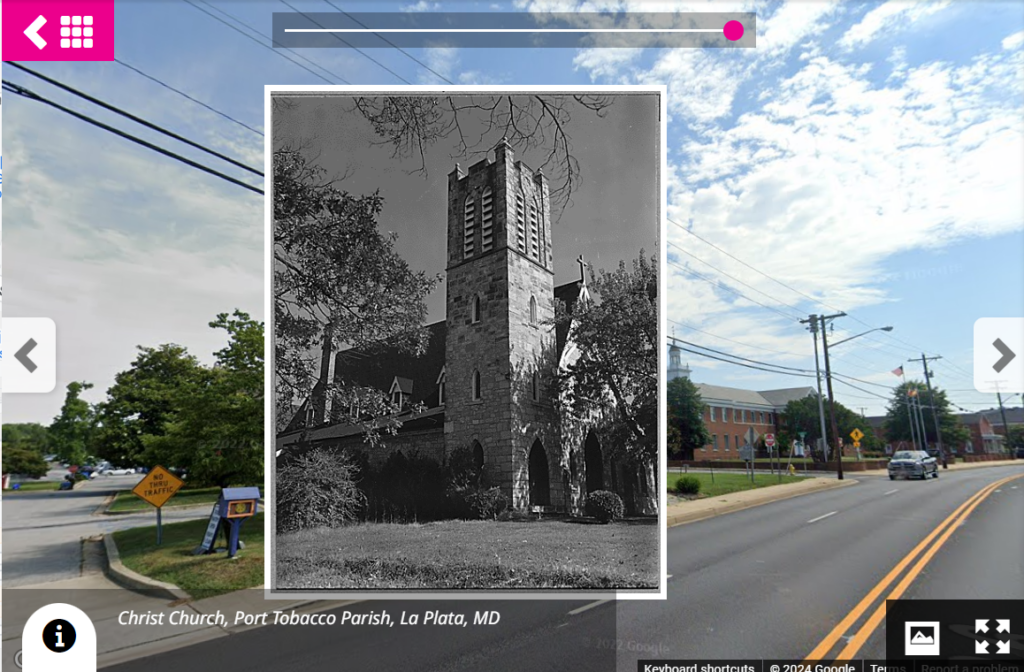

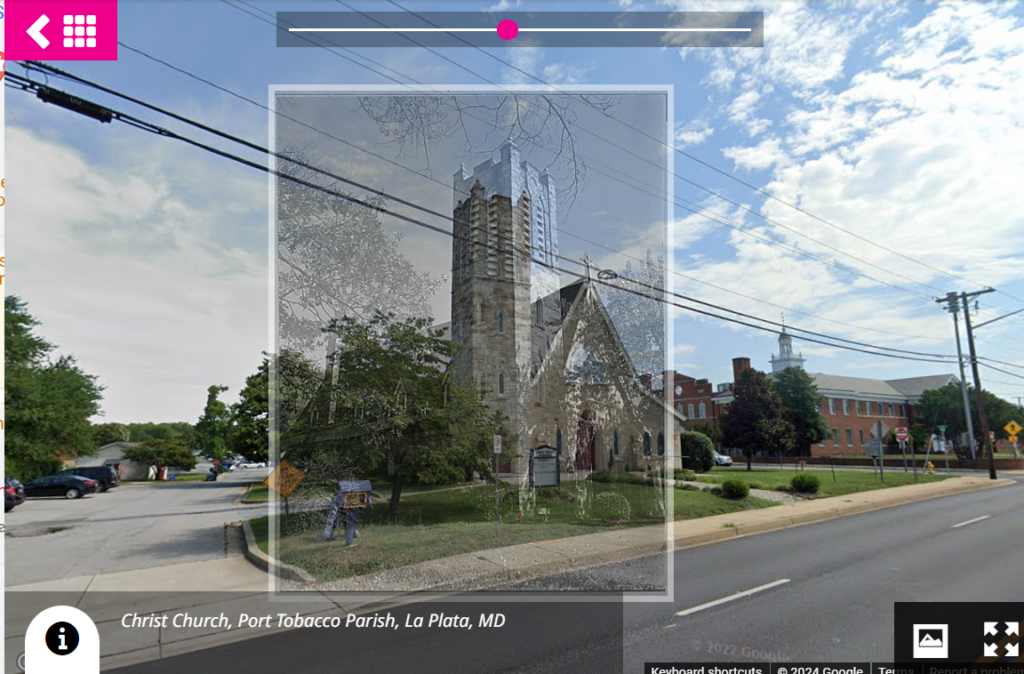

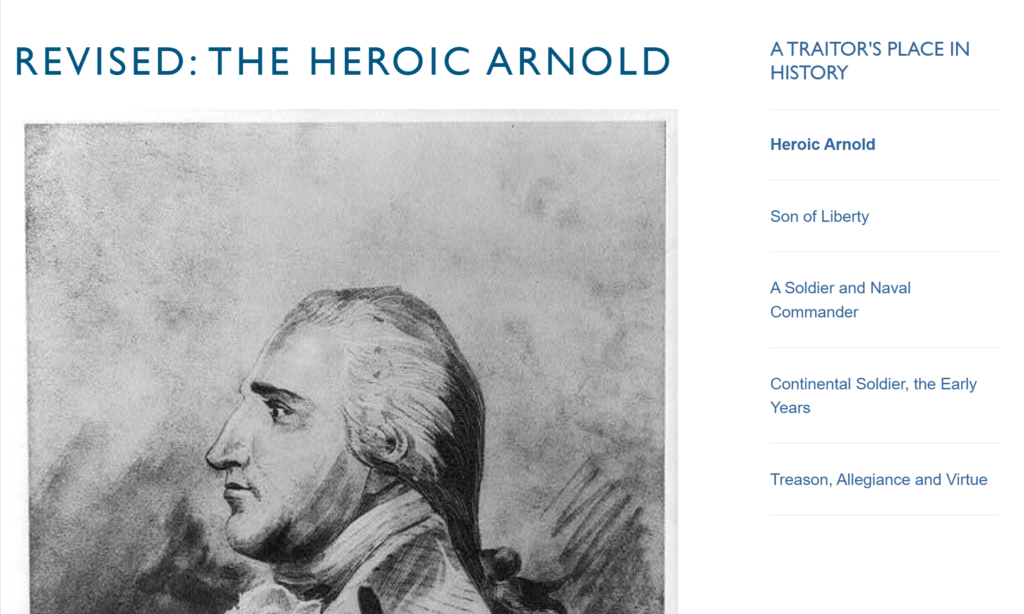

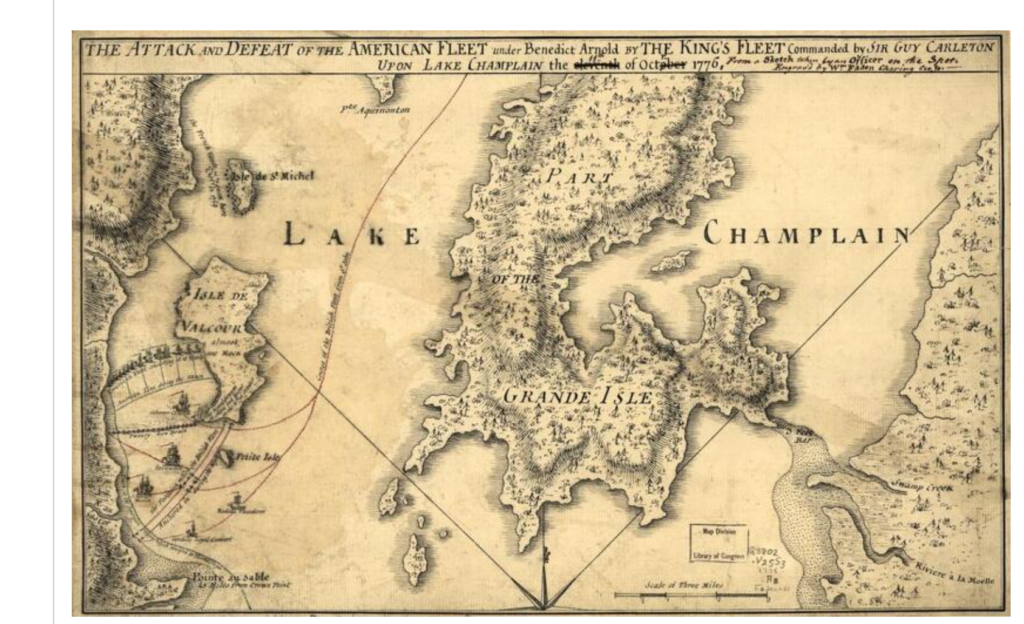

Historians like Carl Becker have responded to technological change in the 20th century by encouraging the expansion of the history profession to the “everyman” or in other words people outside of academia. Becker understood that traditional representations of history were competing against “radio shows, newspaper headlines and suit pockets” (p.508). Edward L. Ayers agrees with Becker. Ayers acknowledges that “ambient history” created with artificial memory has increased with digital media. Online forums, genealogy, documentary, video games, and podcasts have revolutionized representations of the past. In the case of the 21st century, historians like Alison Robinson responded to events like Covid-19 by having her students carry on with their history learning through digital media. In reaction to the pandemic, Robinson had her students create a digital history project using WordPress as an online exhibit platform. Robinson’s project served as an extension of the instruction her students experienced in class. The students had to conduct original historical research using material culture with readings, class discussions, museum visits, and object handling experience. They then had to combine and adapt their historical knowledge with the making of a digital exhibit where they had to consider a target audience and share their research and digital creations.

External expectations associated with national politics and educational standards have constrained the teaching and learning of history. National politics has placed history at the center of national debates. Heated discussions occur as a means of determining what type of history should be taught in schools. Standardized tests also change the way history is taught by placing an emphasis on multiple choice questions that require the retention of facts as opposed to in depth historical interpretations. The results of these standardized tests also cause alarm on the national landscape and push for more reforms in history education. Consequently, educational standards are developed to reflect the political trends. Questions on whether history should tell the “truth”, be patriotic, or recite the facts are debated. Textbooks, the primary teaching tool of many history teachers, are created to reflect the educational standards as well as the politics of the time.

The digital might disrupt these constraints by making history more engaging for students. The digital can also allow students to elevate their learning through digital projects. Digital technology such as mobile applications, podcasts, and video games can enhance historical understanding. Just like with Robinson’s students, digital media can foster enriched learning activities that call for students to expand on their built historical knowledge and utilize their skills of contextualization and interpretation.